WAGNER'S WORKS

WAGNER'S WORKS

Introduction.

Wagner’s dramatic works, whose composition, performance, and theoretical foundation almost filled up his life, have not only strongly influenced the contemporary and subsequent history of opera up to Richard Strauss, Claude Debussy and Alban Berg, but have also left clear traces in the literature and philosophy of the subsequent period (Nietzsche, Thomas Mann, Ernst Bloch, Theodor W. Adorno). His style of composing continually developed into more and more complex creations, especially in the area of melody, harmony, instrumentation, (guiding) theme structuring and form disposition. His music, his aesthetic ideas and his self-image as an artist gained influence over contemporary composers und successors (Anton Bruckner, Hugo Wolf, Gustav Mahler, Hans Pfitzner) up to the phase of the radical change to New Music (Arnold Schönberg). These elements are considered the prototypes of romantic art imagination and are still present as contrast and background in the shape of sharp oppositions from a later time (Debussy, Strawinsky). Wagner’s creative opera work can be arranged into three periods.

Syquali Crossmedia AG

Seestrasse 261, 8038 Zurich, Switzerland

office@syquali.ch

©Syquali Crossmedia AG, 2019.

1st Period 1834–1840. In the first period he adapted forms and attributes of the genre that he found in his contemporaries’ works. His first stage piece, “The Fairies” (1834, after Carlo Gozzi), is a romantic opera in a similar style to Heinrich Marschner’s; the second, “The Ban on Love” (1836, after Shakespeare’s “Measure for Measure”), was a half buffonesc, half revolutionary adaptation of Italian and French role models. For both operas, Wagner wrote the texts himself, as he did for each and every one of his dramatic works. Wagner considered the texts early preliminary stage trials.

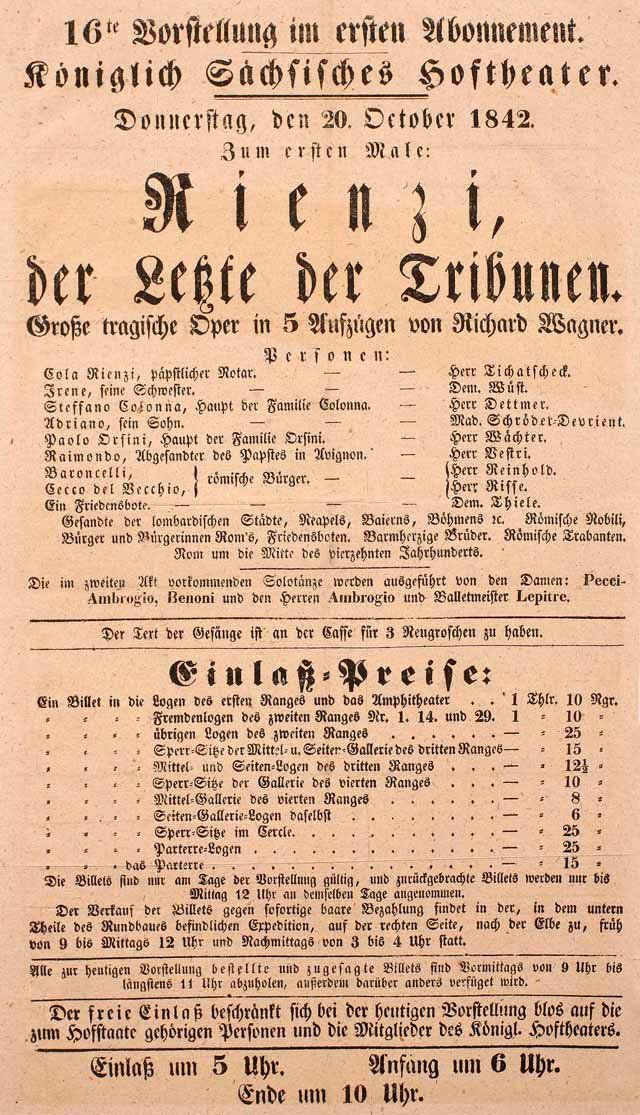

In contrast, in “Rienzi” (1840, after Edward Bulwer-Lytton) distinct stylistic characteristics of his maturing period were visible, even though the construction and habit still drew on the French Grand Opéra.

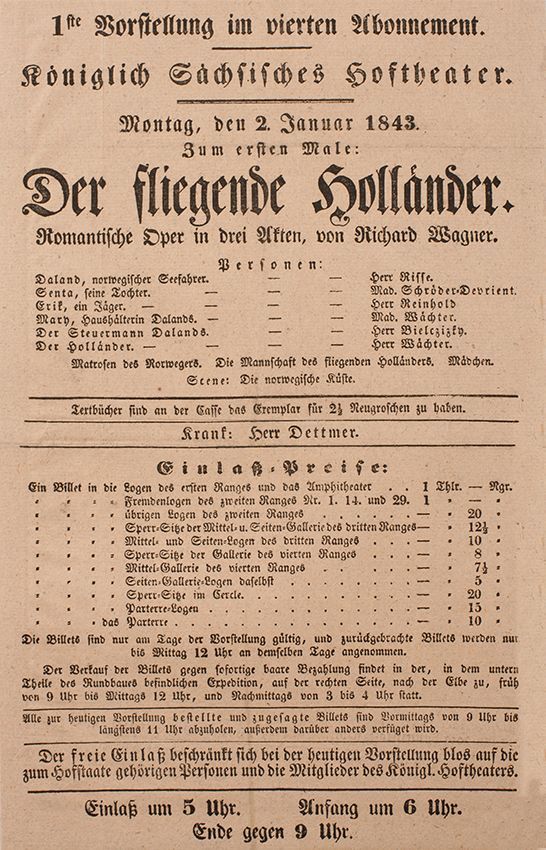

2nd Period 1841–1848. The second period starts with the opera “Der Fliegende Holländer” which was composed in Paris and premiered in Dresden. Distinct elements of Wagner’s later works are already clearly visible here: the thematic basis of the myth, the characters who tend towards the demonic and grand, the idea of salvation through love lasting beyond death, a dramatically inspired pathos, an expressive orchestra language which is integrated into the plot through the different acoustic colours and the suggestive motive conjunction, as well as the aim, surpassing Weber and Marschner, to conquer the traditional opera through grand, organically joined scenes. In “Tannhäuser” (1845), whose subject originates in the romantic notion of medieval Germany, salvation is antithetically imbedded in the tension between sensual entanglement and pure chaste love.

From a compositional point of view there is an increased tendency towards grand form shaping, specific sound characteristics and individual speech melody (for example in the “Rom-Erzählung”). “Lohengrin” (1848), the last work of this romantic period, takes up an element of the grail legend and connects the idea of salvation with the motive of faithful, unconditional devotion and love. The mostly through-composed opera forms the impending pre-stage to the music dramas of the third period of Wagner’s works.

A creative break followed this period, the first part of the Zurich exile, in which Wagner extensively developed his idea about the music drama by means of art theory. This topic is particularly dominant in “Oper und Drama” (1851), which he propagated (drawing on his thoughts about the literary romantic period) as a total work of art where single art forms, in particular poetry and music, blend into a whole through mutual inspiration. Alliteration and free meter are combined to create, on the one hand, a melody that does not follow given structures; on the other hand, they are joined to become a “poetical and musical period” that is committed only to the psychological situation on stage, in the shape of a free flow, similar to prose. The singing avoids genres like recitative and aria, and becomes a dramatically inspired “infinite melody” that is carried by a profoundly interpreted, harmonically differentiated texture of the orchestra. A crucial element that constitutes form and meaning is the “leitmotif”. The term was first introduced into the Wagner literature by Hans Freiherr von Wolzogen in 1876. Wagner himself used terms like “main theme” or “inkling motive”, which becomes a medium of intricate relationships and surprising interpretations of the dramatic events through repetition, various changes, new lighting and linking with other motives.

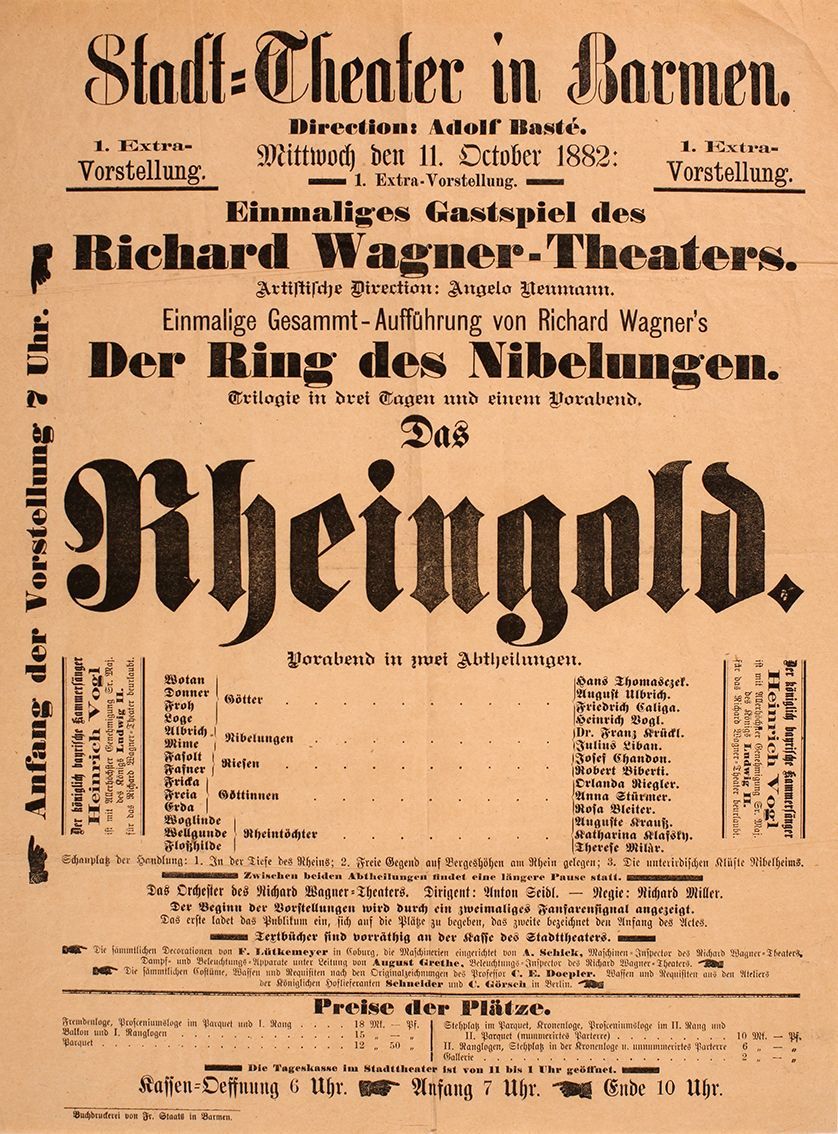

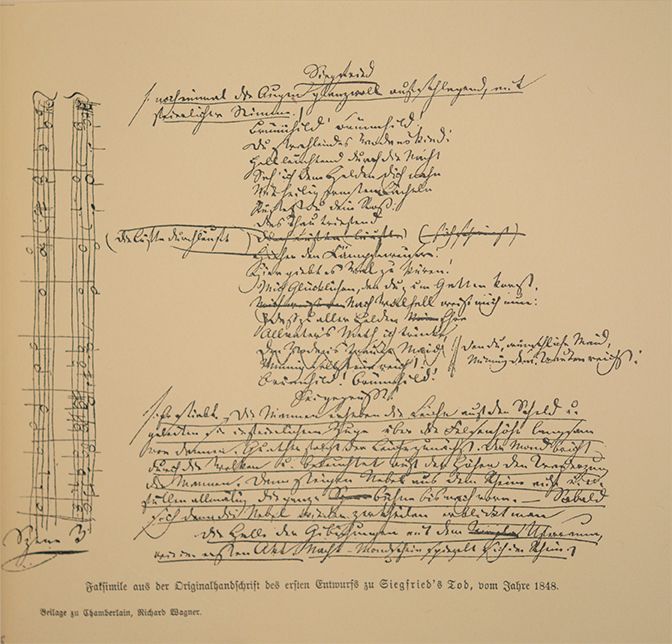

3rd Period 1849–1882. The third period starts with the work on “Der Ring der Nibelungen” which realises Wagner’s theories musically. He drew the subject matter from the Germanic gods’ and hero tale. However the characters and motives of this tale are updated and symbolically compressed under the influence of anarchistic utopian (Pierre Joseph Proudhon), revolutionary (Michail Bakunin), atheist (Ludwig Feuerbach) and pessimistic trends (Arthur Schopenhauer). The idea these trends helped develop, namely to join four colossal operas in a cycle (Wagner refers to it as a “trilogy” with a “prelude”), happened slowly through the realisation that the original draft of “Siegfrieds Tod” (later “Götterdämmerung”) would only be musically and poetically comprehensible as the conclusion of encompassing events, including the premise of the original pilferage of the Rhine gold through the Nibelung Alberich. Thus the complete text was written until the end of 1852, based on drafts from 1848, and was followed by the composition of the opera “Das Rheingold” (1853/54), “Die Walküre” (1854/56) and almost two acts of “Siegfried” (1856/57), before the work was completed with the end of “Siegfried” (1864/71) and “Götterdämmerung” (1869/74) after a long break.

While the work on the “Ring” lay still (its eventual completion was closely linked with the realisation of the festival idea since an appropriate performance was unimaginable beforehand), Wagner wrote two further operas, which may have followed the principles of music drama, but were clearly different from each other as well as the Nibelung trilogy. “Tristan und Isolde” (1859) is an extraordinarily philosophically and psychologically inspired stage play. Early romantic notions of the metaphysics of night and death, as can be found in Novalis’ “Hymnen an die Nacht” (1800), are radicalised in this opera and connected with Schopenhauer’s fundamental idea of the negation of the will to live in a curious way. And even this idea is fundamentally reinterpreted to yearning for togetherness in death after a liberated night of worldly love, especially after “Trug des Tages”. Unlike the “Ring”, musically “Tristan und Isolde” is concepted symphonically. Instead of a definable guiding theme the orchestra score develops as permanent execution and inexhaustible variation of a compositional original idea, which is defined by absolute chromatisation as well as an alteration harmony which almost crosses the limits of tonality, a characteristic that was already exemplary in the Tristan chord at the beginning of the prelude.

“Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg” (1867) in comparison appears more plastic, lucid, as well as scenically and musically stronger structured. The art of the transition, the finely nerved orchestra language of the Tristan score may enter as an artistic experience, but Wagner again also makes use of closed forms (song of praise, Fliedermonolog), even ensembles and choirs; however the complete work is made into a tonally clearer, sometimes diatonal harmony. The plot springs from an idealised depiction of late medieval urban bourgeoisie with its guild-bound and regulated artistry. It is this artistry that is externally questioned by the near ingenious knight Walther von Stolzing, and is inwardly led to a new artistic veracity by the world-wise cobbler and poet Hans Sachs. Stolzing’s eventually won singer mastership, namely the incorporation of spontaneous creative production, exemplifies Wagner’s personal aesthetic position. At the same time this opera conveys a great amount of the German-national sense of self, which too easily fell victim to the danger of reinterpretation in the sense of Third Reich ideology.

A last impressive step in Wagner’s music-dramatical work is the late work “Parsifal” (1882), whose sacral intention as a “stage consecration festival” and the idea of salvation, which was turned into a Christian element, was the focus of Nietzsche’s abrasive criticism from the very start. Solemn calm forms the work’s undertone, to which despair and pain, sensibility and sin establish extremely stark contrasts. The spatial effect of hymnal chordality and far-spread melodic lines refers to the sensibility, whereas intense chromaticism and alteration harmony set up the opposition used to depict hopelessness and the longing for salvation. But also the seductive sphere of Klingsor is symbolised through iridescent, chromatic tonality, which virtually turns the Tristan reminiscences into something sensually renegade. Polyphone traces of the orchestra score and a sporadically very harsh, functionally barely interpretable harmony, especially also in long, muted, recitative parts, are characteristics of a late style, also in the sense of compositional development of the 19th century in general. There is no other example in stage literature for the two-faced penitent and seductress Kundry, whose singing part touches the listener by ranging from extreme such as whispering and stammering to wild screams, and hence had a great influence on later opera compositions, like for example Richard Strauss’ “Salome” (1905) and Alban Berg’s “Wozzeck” (1925).

Works catalogue

Dramatic Works.

Die Feen (1833-34, UA 1888); Das Liebesverbot (1835-36, UA 1836); Rienzi (1838-40, UA 1842); Der fliegende Holländer (1841, UA 1843); Tannhäuser und der Sängerkrieg auf der Wartburg (1842-45, UA 1845, Neufassung 1847, Neufassung für Paris 1860); Lohengrin (1845-48, UA 1850); Tristan und Isolde (1857-59, UA 1865); Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1861-67, UA 1868); Der Ring des Nibelungen: Das Rheingold (1853-54, UA 1869); Die Walküre (1854-56, UA 1870); Siegfried (1856-57, 1864-71, UA 1876); Götterdämmerung (1869-74, UA 1876); Parsifal (1877-82).

Oratorical Works.

Das Liebesmahl der Apostel (1843).

Songs.

Fünf Gedichte (Mathilde Wesendonck) für eine Frauenstimme (1858). Orchesterwerke: Sinfonie C-Dur (1832); Eine Faust-Ouvertüre (1840, Zweitfassung 1855); Siegfried-Idyll (1870); Kaisermarsch (1871).

Writings.

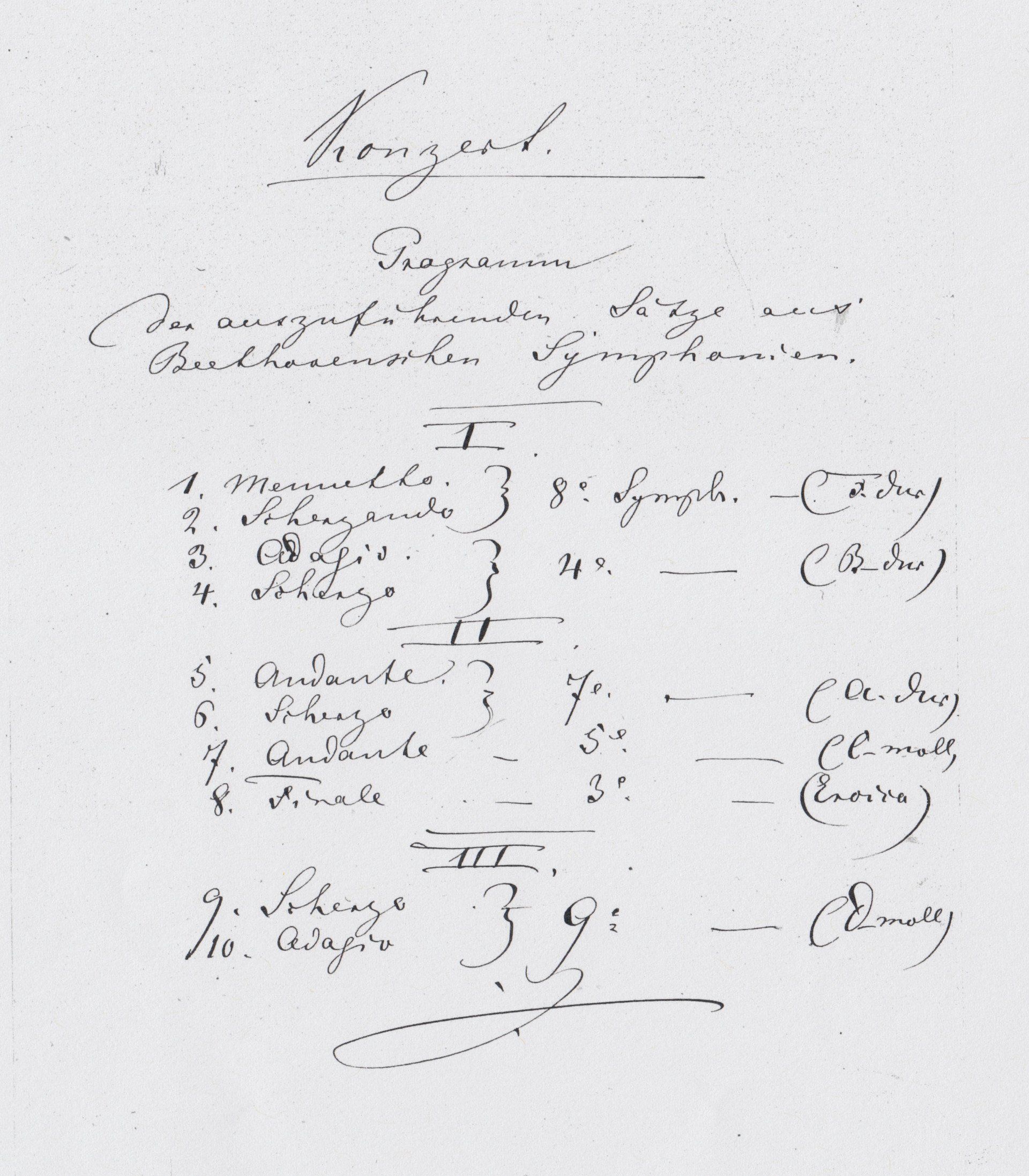

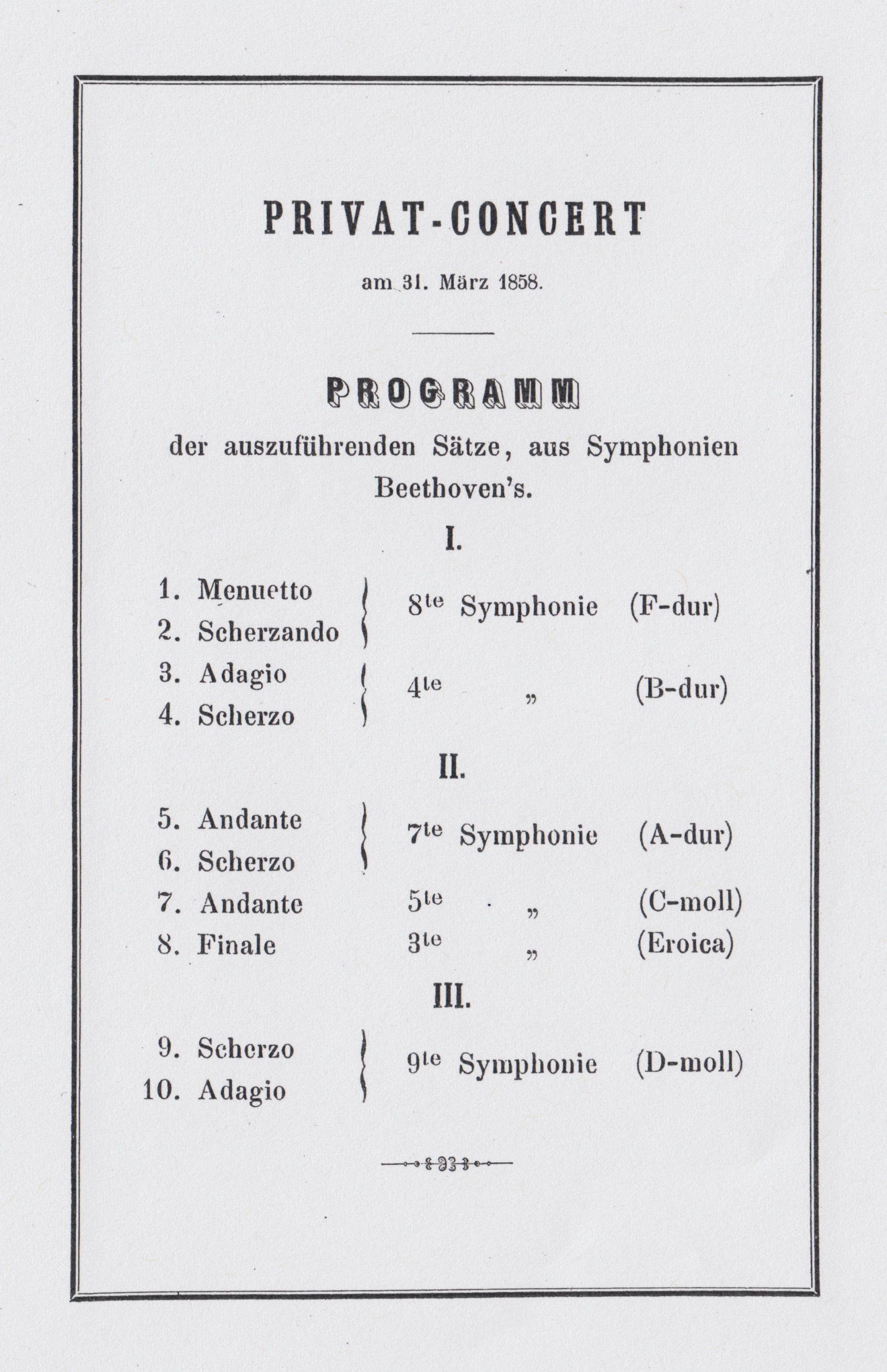

Ein deutscher Musiker in Paris (1841); Die Wibelungen. Weltgeschichte aus der Sage (1848); Der Nibelungen-Mythos (1848); Die Kunst und die Revolution (1849); Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft (1850); Das Judentum in der Musik (1850); Oper und Drama (1851); Eine Mitteilung an meine Freunde (1851); Zukunftsmusik (1860); Über Staat und Religion (1864); Deutsche Kunst und deutsche Politik (1868); Mein Leben (1865-80, Privatdruck in 4 Bänden, 1870-80); Über das Dirigieren (1869); Beethoven (1870); Religion und Kunst (1880).

SYQUALI CROSSMEDIA AG, SEESTRASSE 261, 8038 ZURICH, SWITZERLAND. OFFICE@SYQUALI.CH

© SYQUALI CROSSMEDIA AG 2021.